Column: What is genocide? How does it happen?

Article 1 of “The Western World Has Never Cared About Genocide" series.

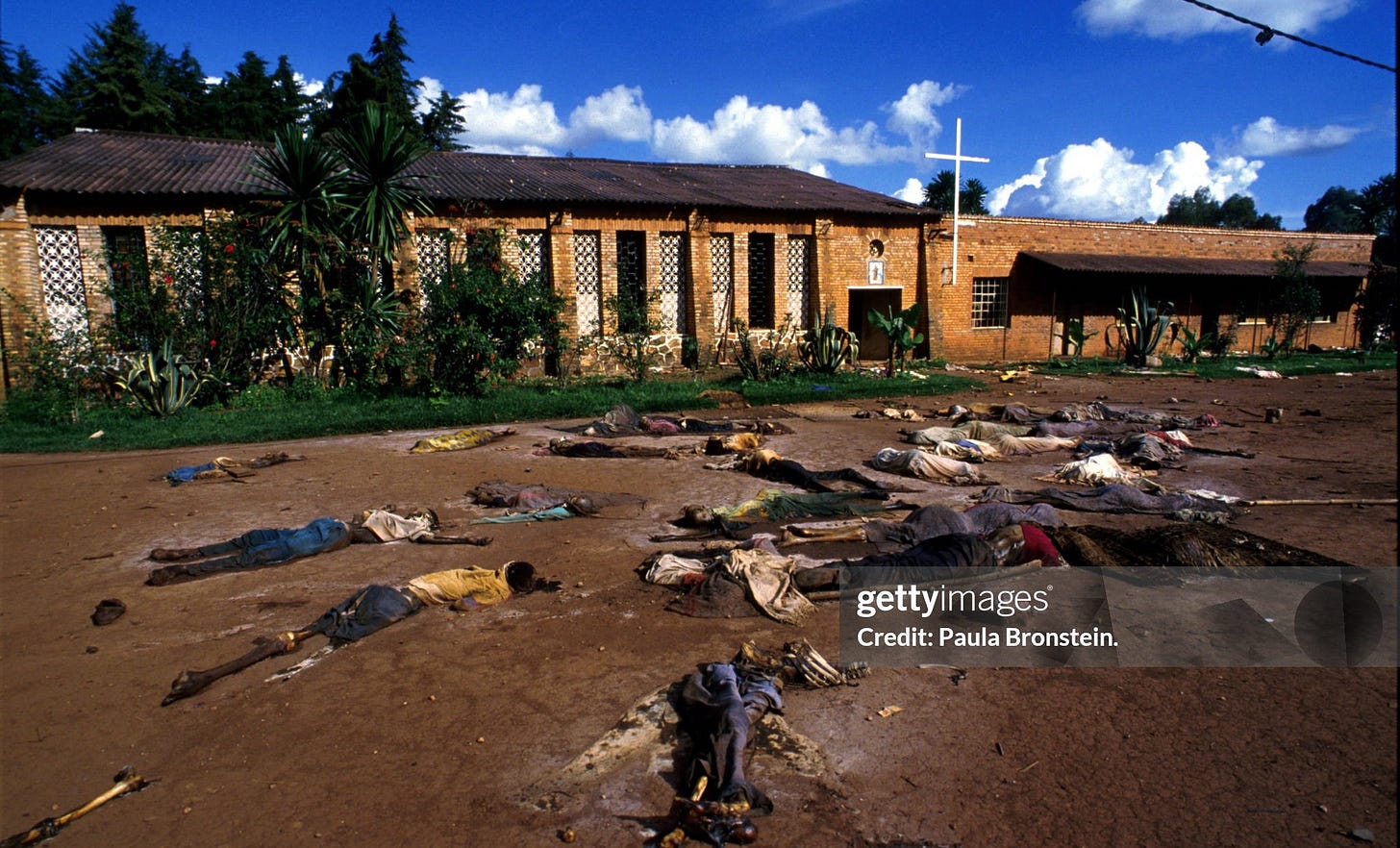

Trigger Warning: This article includes mentions and images of genocidal killings and human remains. Please proceed with caution if you are sensitive to these subjects.

For most people, when thinking of the word genocide, it is easy to recall at least one example — the Holocaust during World War II – in which approximately 6 million people were murdered en masse under the Nazi regime in central Europe.

Some may think of the Rwandan Genocide of 1994, in which, over the course of 100 days, 800,000 Tutsis were slaughtered in the streets of the small, landlocked country by neighbors, friends, coworkers, even family members.

Perhaps others think of the Cambodian Genocide, the systemic persecution and killing of 1.5 to 2 million Cambodian citizens by their ruling communist government, or the Armenian Genocide, in which Turkish occupying forces of the Ottoman Empire killed between 664,000 and 1.2 million Armenians during World War I.

But for many in Generation Z, when thinking of the term, it is most closely tied to the ongoing Israel-Palestine conflict.

The word genocide is actually a very young word, having been first used following World War II to describe the Holocaust. Around two thirds of the Jewish population were forced into concentration camps and systematically murdered by Nazi Germany and their collaborators in Nazi-occupied central Europe between 1941 and 1945.

A Polish-Jewish author named Raphael Lemkin published a book in 1945, entitled Axis Rule in Occupied Europe. The book was the first written place where the word was used. The word combined the Greek geno-, meaning tribe or race, and the Latin -cide, meaning killing.

Following the release of Lemkin’s book, the term genocide became a legal word used to define a specific international crime – the systematic killing of a large group of people with the intent to destroy or eliminate said group.

Whether the reasons for the onslaught of killings is religious and cultural differences, such was the case during the Holocaust, or because one group thought themselves superior to the other simply because they had more in numbers, such was the case during the Rwandan Genocide, it is hard to imagine that there are any excuses in which such a crime could ever be justified.

So, if it is so frequently an unjustified crime, how could something so unimaginable ever take place? Well, for starters, it doesn’t happen overnight.

In 1996, Gregory H. Stanton, Ph.D, former President of the International Association of Genocide Scholars, wrote a document at the US Department of State entitled Eight Stages of Genocide, which was revised in 2013 and changed to the Ten Stages of Genocide, according to the Genocide Education Project. It is important to note that these stages may not happen within the order that they are listed. In fact, it isn’t unheard of for several of these stages to happen simultaneously.

The first stage is classification. People are different from one another. Groups of people differ from other groups. When a minority group within a region, country, or other area is not respected, an “us versus them” mindset may be formed using stereotypes, creating a divide in society.

The second stage is symbolization. Among the most notable examples of symbolization taking place would be the star of David that European Jewish people under the Nazi regime were made to wear to easily identify them as Jewish.

This is to create a visual identifier to further societal divides, feeding into the mindset established at first with classification. For example, during the Rwandan Genocide, the government issued papers to citizens that identified them as Hutu or Tutsi.

In 1994, Rwandan Tutsis accounted for 14% of the population, and Rwandan Hutus accounted for 85% of the population. Tutsis ruled Rwanda as the “superior” group for centuries. Following World War 1, they were backed by Belgium, but when a democratic government was established in 1962, the Tutsi monarchy was replaced with the popularly elected Grégoire Kayibanda, an ethnic Hutu who established a de facto one party system and was later overthrown by the Hutu Power supremacist, President Juvénal Habyarimana.

The third stage is discrimination. Taking place typically systematically, the marginalized group in the area may be denied their rights by a dominant group using societal customs or political power. They may be stripped of their civil rights and even their citizenship.

The 1935 Nuremberg Laws discriminated against German Jewish people by stripping them of their citizenship and made it illegal for Jewish people to hold government and university jobs.

Dehumanization follows discrimination. The fourth stage makes it easier to justify acts of violence against the marginalized group by stripping their humanity from them and labeling them as less than, often comparing them to animals. It is typically done through propaganda and has been recorded multiple times throughout history.

The propaganda villainizes the victims, like when the Tutsi people were labeled as cockroaches during the Rwandan Genocide.

Organization is the fifth stage. It happens in many ways and may be societal or political. Violent mobs committing crimes against marginalized groups and their property, may be overlooked by police and government officials, and may even be subtly or, less often, outright encouraged. State-sponsored militias, like the Hutu Power – a supremacist group called the Interahamwe throughout Rwanda – may also pop up.

At this point, genocidal killings are starting to be mapped out.

The sixth stage is polarization. A tactic also used to further divide society and reinforce the “us versus them” mindset, the victimized group are typically demonized through propaganda.

Anyone who chooses the “wrong side” or doesn’t openly support the “right side,” is targeted by militias and other extremists. Those deemed as sympathetic to the marginalized group may be ousted by their communities, attacked or wrongfully arrested. And if a politician is deemed to be “too moderate” or sympathetic to the victimized, they are often among the first to be assassinated.

The seventh stage is preparation. Those in the targeted group may be identified by their names or numbers assigned to them throughout this stage. Weapons are acquired and stockpiled for the upcoming genocidal killings. Militias and militaries are training and fear-mongering propaganda is further spread, often pushing the message of, “if we don’t kill them, they will kill us.”

Throughout the eighth stage of persecution, those within the marginalized group may be subjected to systematic harassment, displacement, and mass arrests or attacks against them.

Using identification papers issued by the Rwandan government, the Interahamwe began to draw up death lists of Tutsis and Tutsi sympathizers throughout the country. Property is often confiscated. It is the stage of persecution where genocidal massacres begin.

Extermination, which many would expect to be the final stage of genocide, is actually only the ninth. In this stage, the tide of mass killings very quickly shifts to the legally defined genocide. The killers fail to see their victims as human beings due to the amount of fear-mongering and propaganda spread throughout the buildup to the outright genocidal massacres.

Unless handled properly, this can easily trigger a second genocide following, where those in the marginalized group attacked the first time rise up and act out revenge killings — murdering those who had murdered them.

Denial. Bodies are burned. Mass graves are dug and destroyed. The killers refuse to admit that they have done anything wrong and deny what happened as well as blaming victims. An international tribunal is established to try them for their crimes. These are all signs of the final stage of genocide: the rewriting of history by the perpetrators.

According to Stanton denial is among the surest indicators of further genocidal massacres.

On the international stage, genocide is said to require a large scale international response in order to “liberate mankind from such an odious scourge,” according to the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. The Genocide Convention is an international contract signed and ratified by 153 countries, both members of the United Nations, and countries who are not members who were invited to sign it by the General Assembly.

The Genocide Convention provides a legal definition to genocide and identifies genocide as an international crime in times of peace or in times of war. Contracting parties agree that they have an obligation to prevent and punish genocide.

The centered argument in the west that there is enough going on in one country and that each country’s rulers should turn their eyes away and keep focused on ongoing issues in one’s country is sound and entirely valid.

However, 153 countries have ratified or acceded to the Genocide Convention as of June 2024, including the United States of America, and if a country is a contracting party, they are legally required to act.

So why are we not acting?

Editor’s note: This article is part of a newsletter series called “The Western World Has Never Cared About Genocide.” Articles in this series will be published over the span of months as these are hard, journalistic pieces by one of our very best writers, Kay Strickland. Subscribe to the newsletter here.

Kay Strickland is a staff writer for The Palmetto. She loves movies and music, though anything that catches her interest becomes a topic she is deeply passionate about.. Her main focuses are concert reviews, literary reviews, and international political and humanitarian crises. If you have a comment or a tip for Kay, feel free to contact her on social media or through email.

Reach Kay at kay@thepalmetto.org